Environmental Stress & Plant Chemistry

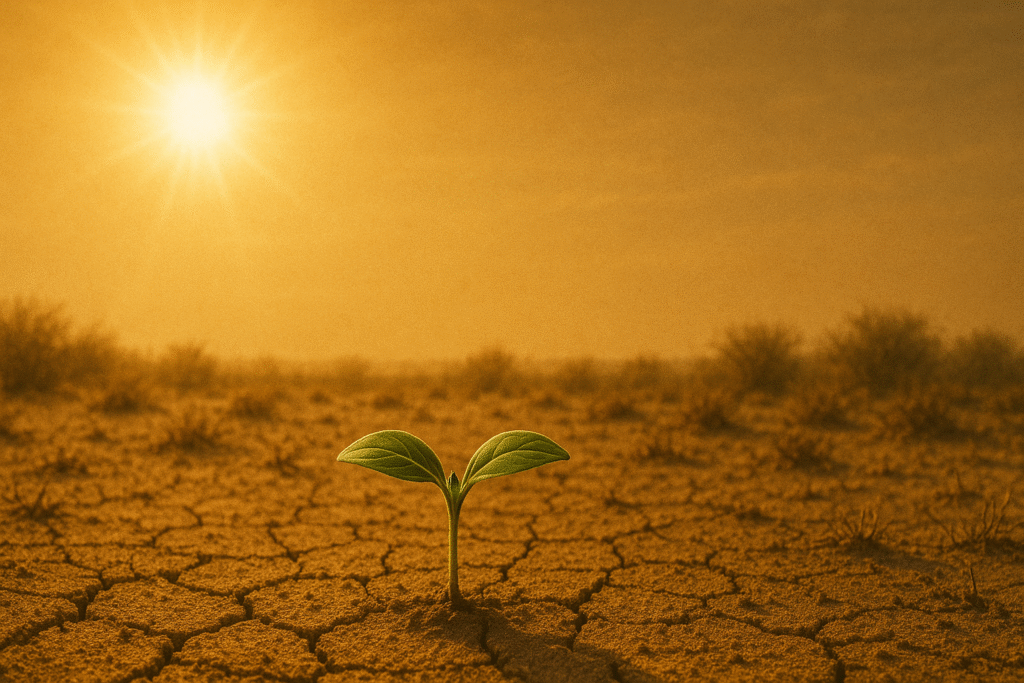

Why Harsh Conditions Create Stronger Botanicals

Plants are remarkable chemical engineers. Unlike animals, they cannot flee drought, heat, insects, UV radiation, or nutrient-poor soils. Instead, they adapt — not by moving, but by building complex defensive chemistry within their own tissues.

This process is the foundation of phytochemistry, and it’s the reason certain environments — especially hot, dry, sandy, nutrient-poor regions like Central Texas — produce plants with higher concentrations of aromatic oils, polyphenols, tannins, terpenes, and protective compounds.

In other words:

Stress builds strength.

And nowhere is this more evident than in the wild botanicals of the American South.

1. Why Plants Make Defensive Compounds in the First Place

Plants produce secondary metabolites — such as terpenes, phenolics, flavonoids, tannins, alkaloids, and antioxidants — not for human benefit, but for their own survival.

These compounds defend against:

- Heat & drought stress (abiotic stress)

- UV radiation

- Oxidative stress

- Insects and herbivores

- Fungal and bacterial threats

- Soil nutrient deficiency

- Mechanical damage from wind or grazing animals

Secondary metabolites act as:

- Natural sunscreens (anthocyanins, phenolics)

- Water retention regulators (osmoprotectants)

- Defense chemicals (thymol, carvacrol, tannins)

- Stress-signaling antioxidants (ellagic acid, rosmarinic acid)

- Aromatic deterrents (terpenes, volatile oils)

In evolutionary terms, the harsher the environment, the more heavily plants rely on chemical defenses.

2. What the Research Says: Stress Elevates Protective Compounds

Across multiple plant families and ecological systems, research consistently shows:

Drought → Increases phenolic content

Plants under water stress accumulate:

- Higher total polyphenols

- Increased flavonoids

- Enhanced antioxidant activity

- More concentrated aromatic oils in Lamiaceae species

This is documented in mint family plants such as Monarda, Thymus, Origanum, and Rosmarinus.

Heat → Boosts aromatic oils and antioxidant responses

High temperatures stimulate production of:

- Terpenes (thymol, carvacrol, linalool)

- Phenolic acids

- Stress-protective pigments

Heat forces the plant to guard its cellular structure, increasing chemical density.

Poor soil → Enhances tannin and phenolic development

Nutrient-poor substrates, such as sugar sand, reduce growth rate but increase chemical complexity.

Plants invest energy into chemical survival, not size.

UV radiation → Triggers anthocyanin and resveratrol-type compounds

This is especially important for fruits such as muscadine, where sun exposure increases:

- Skin thickness

- Pigmentation density

- Antioxidant compounds

Fungal pressure → Encourages defensive phenolics

Plants in humid, fungal-prone regions (like the Southeast) develop:

- Thicker skins

- More tannins

- Stronger antimicrobial secondary metabolites

This is why muscadine, a grape adapted to humid Southern forests, developed chemistry far stronger than European grapes.

3. Stress Physiology: How Plants Convert Hardship Into Chemistry

Oxidative Stress → Antioxidant Production

When a plant faces heat, drought, or UV radiation, reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulate.

To survive, the plant increases synthesis of:

- Flavonoids

- Phenolic acids

- Anthocyanins

- Ellagitannins

- Terpenoid antioxidants

This biochemical cascade makes the plant more resilient — and also increases the concentration of compounds researchers study today.

Mechanical & Herbivore Stress → Volatile Oil Production

When insects feed or wind breaks tissue, plants synthesize volatile oils as:

- Deterrents

- Antimicrobials

- Rapid-response defense chemicals

This is documented extensively in Monarda, Thymus, and Origanum species, where thymol and carvacrol production increases under repeated environmental pressure.

Water Deficit → Concentration of Oils & Polyphenols

Drought reduces water content inside plant tissues.

This does two things:

- Increases potency per gram of plant material

- Triggers deeper chemical storage in the tissues

In wild Texas horsemint, this often results in:

- Higher thymol percentages

- Higher p-cymene and γ-terpinene levels

- More robust aromatic density

In muscadine, drought encourages:

- Thicker skins

- Higher tannins

- Stronger pigment formation

- Increased phenolic content

4. Texas: A Stress Ecosystem That Builds Potent Plants

Central Texas presents an extraordinary combination of environmental pressures:

Extreme Heat

100–110°F summers intensify aromatic oil production and phenolic density.

Drought Cycles

Irregular rain patterns force plants to adapt chemically, not physically.

Sandy, Nutrient-Poor Soil

Sugar sand doesn’t hold nutrients or water, stressing roots continuously.

Wind Exposure

Frequent mechanical stress increases volatile oil activity in mint family plants.

High UV Exposure

Intense ultraviolet radiation increases pigmentation and antioxidant synthesis.

Insect & Fungal Pressure

High humidity and warm nights encourage defense compounds in:

- Grapes

- Mints

- Native shrubs

- Wildflowers

Together, these factors create what botanists call a chemical stress crucible — an environment where plants must build stronger, more resilient chemistry to survive.

This is why Monarda punctata and Vitis rotundifolia from Texas sandy soils frequently show richer phytochemical profiles than their cultivated or irrigated counterparts.

5. Case Studies: Horsemint & Muscadine Under Stress

Horsemint (Monarda punctata)

Native to sandy prairie habitats, horsemint thrives in:

- Full sun

- Dehydrated soils

- High heat

- Wind

- Nutrient-scarce conditions

Stress increases its:

- Thymol (major antimicrobial phenolic)

- p-Cymene & γ-terpinene (synergistic aromatic oils)

- Total volatile oil content

- Minor constituents like linalool and geraniol

This is why wildcrafted or drought-grown horsemint often shows stronger aromatics than irrigated or shade-grown plants.

Muscadine (Vitis rotundifolia)

Muscadine produces the highest phenolic content when exposed to:

- High UV

- Rain/drought variability

- Sandy or acidic soils

- Southern fungal pressure

Stress increases:

- Ellagic acid

- Ellagitannins

- Anthocyanins

- OPC tannins

- Skin thickness

- Seed chemical richness

Muscadine isn’t just tougher than European grapes — its entire biochemistry reflects a plant adapted to survival through chemical strength.

6. Why Stress-Grown Plants Differ From Cultivated Plants

Cultivated plants are often:

- Irrigated

- Fertilized

- Shaded

- Protected from insects

- Bred for sweetness, not strength

- Grown for size, not chemical richness

These conditions reduce chemical stress, which reduces:

- Aromatic oil concentration

- Phenolic density

- Pigmentation depth

- Skin thickness

- Tannin complexity

Wild plants — or plants grown under natural stress — are chemically richer because they have to be.

7. Ecological & Research Significance

Environmental stress is now recognized as one of the key drivers of:

- Phytochemical evolution

- Antioxidant biosynthesis

- Aromatic oil enhancement

- Plant-pathogen defense strategies

This means regions like Central Texas — once considered tough growing environments — are now areas of botanical interest, producing plants with exceptional chemical profiles.

Conclusion: Stress Creates Stronger Plants — By Design

From the mint-covered prairies to muscadine-laced fencelines, the plants that survive the Texas heat do so by building deep, potent, adaptive chemistry.

Environmental stress doesn’t weaken these plants.

It forges them.

And understanding that relationship — between land, stress, and phytochemical response — is essential for anyone studying or working with wild botanicals.

This is why HK Naturals Research continues to document environmental factors, phytochemical data, and ecological influences that shape the plants growing on our land.